Articles

The Bristol Scene

How Bristol's graffiti and street art scene developed from the 1980s through Operation Anderson and beyond.

Bristol had a graffiti scene before most British cities knew what graffiti was.

This isn't mythology. It's geography and economics. Bristol was a port city with cheap rent, post-war bomb sites, and a multicultural population. The conditions were right for subcultures to develop.

How It Started

In 1983, a film called Wild Style showed at the Arnolfini cinema in Bristol. It depicted New York's graffiti and hip hop scene. The same year, a book called Subway Art was published, documenting the New York subway writers.

A Bristol artist called Robert Del Naja - later known as 3D, later a founding member of Massive Attack - had already been to New York and seen graffiti firsthand. He started painting in Bristol.

People who saw Wild Style walked out of the cinema and saw 3D's work on the walls. Several graffiti crews formed that night.

Barton Hill

Barton Hill was a working-class estate in east Bristol. It had a reputation. If you weren't from there, you didn't go there.

A youth worker named John Nation ran the local youth club. The building was covered in National Front emblems and football hooligan tags.

Two local kids asked if they could paint the walls with graffiti instead. John said yes.

The youth club became an unofficial headquarters. Artists could paint legally on the ball court walls. They could practice techniques. They could meet other writers. And they could use the club as a staging point for illegal painting on trains and walls across the city.

Operation Anderson

By the late 1980s, Bristol's graffiti scene was visible enough to attract police attention.

In the summer of 1989, British Transport Police launched Operation Anderson - the biggest anti-graffiti operation ever undertaken in the UK. A total of 72 people were arrested and charged with criminal damage.

John Nation was interrogated. The police wanted him to reveal the real names behind the tags. He refused. They charged him with conspiracy to organise and incite criminal damage.

Most of the arrested artists stopped painting. A smaller group went deeper underground.

What Came After

The writers who continued after Operation Anderson operated differently. More careful. More anonymous. More aware of consequences.

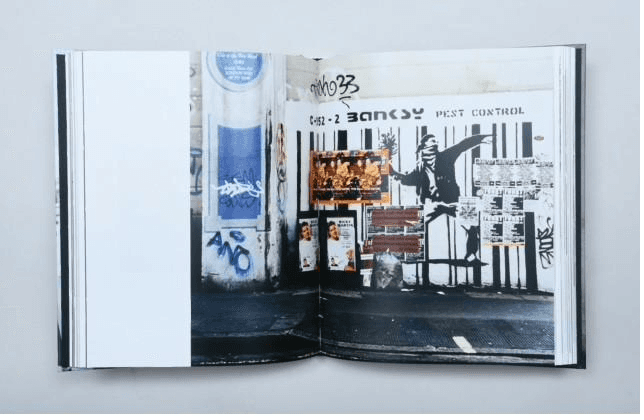

This was the scene that existed when Steve Lazarides started photographing it in the late 1990s. A scene shaped by police raids, legal consequences, and the need for secrecy.

The anonymity wasn't marketing. It was survival.

The Broader Context

Bristol's graffiti scene didn't exist in isolation. It was connected to:

Music. The Wild Bunch sound system, which became Massive Attack. Tricky. Portishead. Trip hop emerged from the same clubs and warehouses.

Politics. Poll tax riots. Criminal Justice Act protests. Anti-war demonstrations. Bristol had an active protest culture.

Free parties. Illegal raves in warehouses and fields. Sound systems. The Traveler community. A whole infrastructure for unlicensed events.

Steve was documenting all of this. The photographs in his books come from this context - a city with a specific history and a specific attitude toward authority.

Why This Matters

Understanding Bristol helps explain what you're looking at in Steve's photographs.

These aren't images from a sanitised art world. They're documents from a scene that was shaped by police raids, class politics, and DIY culture.

The books don't explain this context. They assume you either know it or you don't. This article is for people who don't.

Articles

The Bristol Scene

How Bristol's graffiti and street art scene developed from the 1980s through Operation Anderson and beyond.

Bristol had a graffiti scene before most British cities knew what graffiti was.

This isn't mythology. It's geography and economics. Bristol was a port city with cheap rent, post-war bomb sites, and a multicultural population. The conditions were right for subcultures to develop.

How It Started

In 1983, a film called Wild Style showed at the Arnolfini cinema in Bristol. It depicted New York's graffiti and hip hop scene. The same year, a book called Subway Art was published, documenting the New York subway writers.

A Bristol artist called Robert Del Naja - later known as 3D, later a founding member of Massive Attack - had already been to New York and seen graffiti firsthand. He started painting in Bristol.

People who saw Wild Style walked out of the cinema and saw 3D's work on the walls. Several graffiti crews formed that night.

Barton Hill

Barton Hill was a working-class estate in east Bristol. It had a reputation. If you weren't from there, you didn't go there.

A youth worker named John Nation ran the local youth club. The building was covered in National Front emblems and football hooligan tags.

Two local kids asked if they could paint the walls with graffiti instead. John said yes.

The youth club became an unofficial headquarters. Artists could paint legally on the ball court walls. They could practice techniques. They could meet other writers. And they could use the club as a staging point for illegal painting on trains and walls across the city.

Operation Anderson

By the late 1980s, Bristol's graffiti scene was visible enough to attract police attention.

In the summer of 1989, British Transport Police launched Operation Anderson - the biggest anti-graffiti operation ever undertaken in the UK. A total of 72 people were arrested and charged with criminal damage.

John Nation was interrogated. The police wanted him to reveal the real names behind the tags. He refused. They charged him with conspiracy to organise and incite criminal damage.

Most of the arrested artists stopped painting. A smaller group went deeper underground.

What Came After

The writers who continued after Operation Anderson operated differently. More careful. More anonymous. More aware of consequences.

This was the scene that existed when Steve Lazarides started photographing it in the late 1990s. A scene shaped by police raids, legal consequences, and the need for secrecy.

The anonymity wasn't marketing. It was survival.

The Broader Context

Bristol's graffiti scene didn't exist in isolation. It was connected to:

Music. The Wild Bunch sound system, which became Massive Attack. Tricky. Portishead. Trip hop emerged from the same clubs and warehouses.

Politics. Poll tax riots. Criminal Justice Act protests. Anti-war demonstrations. Bristol had an active protest culture.

Free parties. Illegal raves in warehouses and fields. Sound systems. The Traveler community. A whole infrastructure for unlicensed events.

Steve was documenting all of this. The photographs in his books come from this context - a city with a specific history and a specific attitude toward authority.

Why This Matters

Understanding Bristol helps explain what you're looking at in Steve's photographs.

These aren't images from a sanitised art world. They're documents from a scene that was shaped by police raids, class politics, and DIY culture.

The books don't explain this context. They assume you either know it or you don't. This article is for people who don't.